Correction of errata in Study 1:

Lippa, R. A. (2005). Subdomains of gender-related occupational interests:

Do they form a cohesive bipolar M-F dimension? Journal of Personality, 73, 693-730.

Richard A. Lippa

Richard Lippa

Psychology Department

e-mail: rlippa@fullerton.edu

Study 1

Data

The data came from Loehlin and

Nichols' (1976) classic behavior genetic study of 839 same-sex twin pairs (351

male pairs and 488 female pairs).2

In the early 1960s these twins completed during their senior year of

high school a number of self-report scales and questionnaires, including

Results

Occupational

preference items that correlated with sex at a level of .15 or greater were

identified as sex-linked, and by this criterion, 43 of 160 occupations were

classified as masculine and 32 of 160 occupations were classified as

feminine. Two principal components

analyses with varimax rotations were conducted, one on masculine items and the

other on feminine items. The analysis

of masculine items yielded five interpretable factors, and the analysis of

feminine items yielded four interpretable factors.3 Table 1 shows occupations that loaded .4 or

higher on each of the five masculine factors in a five-factor solution and on

each of the four feminine factors in a four-factor solution. A small number of items that loaded highly on

more than one factor were eliminated.

--------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 1 about here.

--------------------------------------------------

Not all masculine and feminine

subdomains were equally represented in the VPI list of 160 occupations. For example, there were only three

sports-related occupations, but there were thirteen blue-collar realistic

occupations. Because the VPI contains a

large, diverse set of occupations, the number of occupations representing each

factor probably roughly represents social reality -- e.g., there are many more

blue-collar realistic occupations than sports-related occupations in the

An overall masculine occupations

scale was computed by averaging individuals' preference for the 43

male-preferred occupations, and similarly an overall feminine occupations scale

was computed by averaging individuals' preference for the 32 female-preferred

occupations. The reliability of the

masculine occupations scale was .84 for all participants, .73 for males, and

.75 for females, and the reliability of the feminine occupations scale was .86 for

all participants, .79 for males, and .69 for females.

Table 2 shows the intercorrelations

of masculine and feminine occupational subdomains scales for men (above the

diagonal) and for women (below the diagonal). Masculine subdomain scales tended

to show both positive and negative correlations with one another, feminine

subdomains tended to show positive or zero correlations with one another for

men and positive and negative correlations with one another for women, and

masculine subdomain scales tended to correlate negatively with feminine subdomain

scales.

--------------------------------------------------

Insert Table 2 about here.

--------------------------------------------------

To reveal the structure implicit in

the intercorrelations in Table 2, principal components analyses were conducted

on masculine subdomain scales, feminine subdomain scales, and overall masculine

and feminine occupations scales.4

These analyses were conducted for males and females combined and for

males and females separately. Two principal components were extracted,

solutions were left unrotated, and factor scores for participants were computed

in all three analyses. Because masculine

and feminine subdomain scale items were selected because of their correlation

with sex, it seemed likely that the first principal component in the

combined-sex analysis would reflect a sex difference factor (i.e., a factor

that tapped the variance shared in common by all items). However, it was not guaranteed that this same

component would emerge in analyses for males only and for females only.

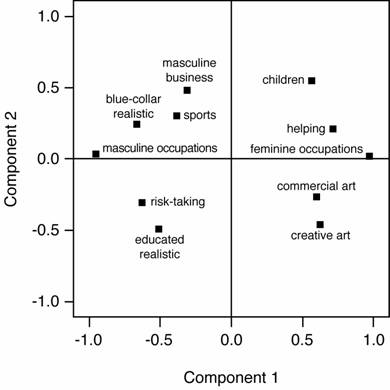

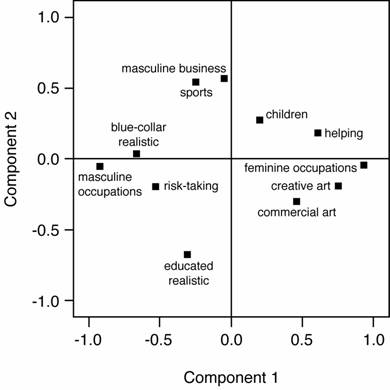

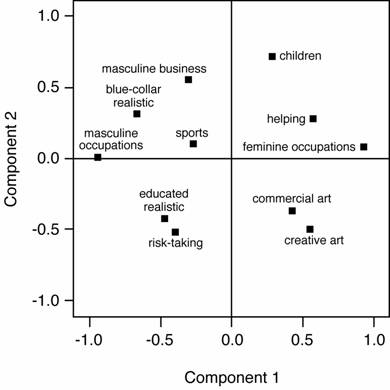

Figure 1 plots masculine and

feminine subdomain scales in the two-dimensional spaces generated by the three

principal components analyses. The first

principal component accounted for 43% of the variance in the combined-sex

analysis, 35% of the variance in the males-only analysis, and 33% of the

variance in the females-only analysis.

The revealed structure was very similar in all three analyses: masculine

subscales tended to lie on one side of the first principal component, and

feminine subscales tended to lie on the other side. The overall masculine and feminine occupation

scales, which served as marker variables, showed that the first principal

component was indeed a "sex difference" factor in the combined-sex

analysis. However, this same factor was

present in the analyses for males only and females only, and in these analyses

the first principal component is best described as an M-F dimension. It is worth noting that subdomain scales

formed a circular arrangement in factor space that was consistent with

--------------------------------------------------

Insert Figure 1 about here.

--------------------------------------------------

To probe the consistency of the

structure generated by the three principal components analyses, participants'

factor scores from the combined-sex analysis were correlated with factor scores

from the males-only analysis and from the females-only analysis. In both cases, the correlation of first

principal component factors scores was close to unity (r = .996 for males and r

= .994 for females, p's <

.001). These extremely high

correlations show that the first principal component identified an individual

difference dimension that was virtually identical in all three principal

components analyses, and they underscore the fact that the "sex

differences" dimension in the mixed-sex analysis was the same as the M-F

dimension in the males-only and females-only analyses.

The second principal component in all

three analyses can be interpreted as a version of the "Ideas-Data"

dimension, with "educated realistic" and artistic occupations (which

entail more creativity and theoretical thought) at one side of the second

component, and "blue-collar realistic," "masculine

business," "helping," and "children-related"

occupations (which involve more practically oriented work) at the other

side. Participants' second principal

component factors scores from the combined-sex analysis correlated highly with

the second principal component factor scores from the males-only analysis (r = .93, p < .001) and from the

females-only analysis (r = .98, p

< .001). The presence of this stable

second factor in all three analyses suggests that there were systematic

non-gender-related influences on the intercorrelations shown in Table 2.

For males and females combined,

masculine occupations were strongly negatively correlated with feminine

occupations (r = -.87, p < .001). Masculine and feminine occupations were also

strongly negatively correlated for males only (r = -.77, p < .001) and for females only (r = -.78, p

< .001) .

Discussion of Study 1

Analysis of the Loehlin and Nichols'

data showed that coherent subdomains of masculine and feminine occupational

interests could be identified from a large set of occupational preference

items. At the same time, structural

analyses of masculine and feminine occupational subdomain scales showed that

masculine subdomains scales tended to lie on one side of the first principal

component, feminine subdomains tended to lie on the other side, and therefore

that masculine and feminine subdomains tended to be bipolar opposites.

The structure of occupational

subdomain scales was highly consistent in all analyses -- for both sexes

combined, for males only, and for females only.

In all cases, the first principal component was gender-related,

reflecting sex differences in the combined sex analyses and individual

differences in M-F in males-only and females-only analyses. The second principal component appeared to

tap a version of the "Ideas-Data" dimension, and the presence of this

second dimension suggests that intercorrelations of masculine and feminine

subdomains scales were systematically influenced by factors other than the

masculinity or femininity of occupations – that is, when masculine scales (or

feminine scales) sometimes correlated negatively with one another, it was

because of differences on the second but not on the first principal

component. Participants' overall

preference for masculine occupations showed a strong negative correlation with

their overall preference for feminine occupations, and this was true whether

correlations were computed for both sexes combined or within each sex.

Table 1

Masculine

and Feminine Subdomain Items and Scale Reliabilities, Study 1

Masculine Subdomains

|

Blue-Collar Realistic |

Educated Realistic |

Masculine Business |

Risk-Taking |

Sports |

|

Airplane mechanic Auto mechanic Carpenter Construction inspector Crane operator Factory foreman Locomotive engineer Machinist Power shovel operator Power station Operator Tool designer Truck driver Wrecker (building) |

Aeronautical design engineer Chemist Electronic technician Experimental lab engineer Interplanetary scientist Physicist |

Bank examiner Banker Business Executive Financial Analyst Sales manager Stock and bond salesman Tax Expert |

Army general Army officer Aviator Counter- intelligence man Racing car driver Test pilot |

Professional athlete Referee (sporting events) Sports promoter |

|

α

= .86, .83, .86 |

α

= .82, .81, .78 |

α

= .74, .77, .66 |

α

= .71, .66, .62 |

α

= .70, .73, .59 |

Feminine Subdomains

|

Helping |

Creative

Arts |

Children-Related |

Commercial Arts |

|

Clinical psychologist Director of welfare agency Juvenile delinquency expert Marriage counselor Personal counselor Psychiatric case worker Social worker Speech therapist Vocational counselor |

Author Concert singer Composer Novelist Playwright Poet Dramatic coach |

Elementary school teacher Nursery school teacher Playground director YMCA secretary |

Art dealer Commercial artist Interior decorator Portrait artist |

|

α = .82, .74, .76 |

α = .80, .80, .77 |

α = .71, .46, .64 |

α = .71, .68, .63 |

Note: Reliabilities (α's) are

for all participants, males, and females.

Table

2

Intercorrelations

of Masculine and Feminine Subdomain Scales, Study 1

|

|

Blue-collar Realist |

Educat-ed Realist |

Masc Busi-ness |

Risk-Taking |

Sports |

Helping |

Creat Arts |

Child-Related |

Comm Arts |

|

Blue-collar Realist |

---- |

-.02 |

-.14* |

.19*** |

.08 |

-.38*** |

-.43*** |

.05 |

-.14** |

|

Educat-ed Realist |

.02 |

---- |

-.29*** |

.05 |

-.15** |

-.19** |

-.20*** |

-.11* |

-.11* |

|

Masc Busi-ness |

.21*** |

-.12** |

---- |

-.12* |

-.03 |

-.07 |

-.13* |

-.10 |

-.06 |

|

Risk-Taking |

.02 |

.17*** |

-.27*** |

---- |

-.01 |

-.24*** |

-.30*** |

-.21*** |

-.23*** |

|

Sports |

.10* |

-.09 |

-.03 |

.15** |

---- |

-.06 |

-.21*** |

.04 |

-.23*** |

|

Helping |

-.40*** |

-.18*** |

-.15** |

-.19*** |

-.13** |

---- |

.21*** |

.12* |

.00 |

|

Creat-ive Arts |

-.35*** |

-.17*** |

-.31*** |

-.10* |

-.17*** |

-.10* |

---- |

.00 |

.32*** |

|

Child-Related |

.07 |

-.34*** |

.09* |

-.33*** |

.07 |

.24*** |

-.16*** |

---- |

.00 |

|

Com-mercial Arts |

-.24*** |

-.15** |

-.17*** |

-.09* |

-.08 |

-.06 |

.34*** |

-.12* |

---- |

Note: Correlations for males are

above the diagonal, and correlations for females are below the diagonal.

* ----- 2-tailed p < .05

**

-----2-tailed p < .01

*** --- 2-tailed p < .001

Figure

1 (Revised)

Plots of

masculine and feminine subdomain scales in two-dimensional component space, for

all participants (top), males (middle), and females (bottom) in Study 1